Translation of《盘点罢工工人被刑拘事件 ——我们唯有团结一致 》(Reviewing cases of strike workers’ detention: we must unite in solidarity) from the “Little iLabour” (小生) WeChat feed, reposted on iLabour here. Translated by Wen for Chuang.

Background: This piece compiles a few examples of a trend toward the increasing criminalization of labor actions in China since 2012. According to the author, this trend could be dated back further to the 2010 nationwide cross-sector strike wave that began in Honda transmission plants, as that was the first time it became common for police to enter factory gates and arrest striking workers (as opposed to arresting them for traffic obstruction, etc., outside factory gates, leaving internal repression to private security guards).1 This trend overlaps with the crackdown on “civil society” associated with the Xi Jinping administration since 2012 (arbitrary criminal detention of feminists,2 anti-discrimination activists and human rights lawyers, forced closure of NGOs, etc.). However, the author believes that the criminalization of labor actions started before Xi came to power, in response to the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent economic concerns, the development of workers’ collective power expressed then and more forcefully in 2010, and fears about growing instability in general. The more recent suppression of other semi-autonomous social forces must be understood in this context. Although all these cases are from the Pearl River Delta, the author believes this trend may apply to China more broadly to some extent, with the armed repression of the 2014 Ningbo port truckers’ strike as different type of example outside the PRD.3

Image from the 2014 Ningbo port truckers’ strike (from the Empire Logistics blog). The caption reads, “Brothers hold it down for me! Those of you across the street, if you don’t move I’ll hit you with the cannon!”

—–

On April 3, 2012, workers at a jewellery factory in Panyu had negotiated for an entire day with the human resources manager about when to make overdue social insurance contributions. The HR manager surnamed He provided a written reply on behalf of management, but workers were not satisfied, and a group of female workers prevented He from leaving the office. In an outburst of anger, He grabbed female worker Xie Liuxian’s hair and pushed her to the ground, and also beat another female worker Xie Yumei. Witnessing the assault on two female workers, their fellow workers called the police. The police took the HR manager and Xie Liuxian to the local police station at 19:20. At 20:00, the police summoned worker representative Cai Manji on the grounds that Xie Liuxian was ‘afraid’. At 20:20, the police summoned Xie Yumei.

At 2:30am on April 4, Xie Liuxian and the HR manager were released, but Cai Manji and Xie Yumei were criminally detained for the next 25 days on the charge of ‘instigating workers to illegally detain’ (煽动工人非法拘禁) the HR manager.

Does the detention of striking workers mean that strike actions are illegal?

It is not clear whether Cai and Xie knew before their detention that cases of striking workers being criminally detained by police are rare in China. But they were fortunate to be released after 25 days, as some striking workers have had to undergo criminal proceedings through court.

On August 19, 2013, a dozen security guards at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine climbed up to a 10-meter-high glass ceiling on the third floor of the hospital. They displayed their banner and distributed leaflets, and used the threat of jumping to their death to pressure the hospital to negotiate.

The previous evening, the security guards had gathered to discuss their struggle, which had started 90 days before. Against the recent compromise made by dozens of care workers at the hospital, one security guard proposed that they should try one last-ditch effort.

This was to use the threat of jumping to pressure the hospital into compromise. Upon hearing this proposal, those present did not immediately support it. At this point, someone said, ‘What are you afraid of? At most, we will only be detained for 15 days.’4

But the next day, the threat by the security guards did not lead to compromise. Instead, the 12 security guards were detained, accused of ‘disturbing the order of public transportation’ (扰乱社会公共交通秩序), and eventually taken to court. The trial resulted in prison sentences of 7 to 9 months. (Most had already been detained for 7 months while awaiting trial, so they were soon released after the verdict. After release, they appealed to change the verdict.)

The security guards had expected to be detained for no more than 15 days because, in the past, such labor actions would be treated as merely a violation of the ‘Regulations on Administrative Penalties for Public Security’, for which the accused may be ‘administratively detained’ (行政拘留) for no more than 15 days. They did not expect to be ‘criminally detained’ (刑事拘留), which applies only to violation of the Criminal Law. In criminal cases, the suspect’s freedom is to be deprived for a prolonged period of time, and the Public Security Bureau and Procuratorate are directly involved in investigation. Such cases sometimes lead to criminal prosecution by the court.

In the past, academics used to debate whether strike actions are legal in China. Each level of the government has also attempted to create a ‘legal strike procedure’ in the legislative process.

But, in the practice of the Public Security Bureau, strike actions are not only illegal, but criminal.

The criminal detention of striking workers as a growing trend

Since the detention of Cai and Xie, it seems that more and more striking workers are being detained.

Apart from the case discussed above, in May 2013, a Shenzhen worker named Wu Guijun was detained during a strike, criminally charged with ‘disturbing public order’ (扰乱社会公共秩序), and put on trial. Although the court found him not guilty, Wu lost a year of his freedom.

During the Chinese New Year in 2014, two worker-representatives in the Guangzhou Donghai Auto Parts factory strike were detained on the criminal charge of ‘disturbing public order’. They posted bail to regain their freedom, but a few months later they were summoned to appear in court. In the trial, even the judge did not understand why the Procuratorate had put them on trial, and how their strike action could be interpreted as disturbing the public order. The judge laughed, seeing through the nonsense, and fortunately the two workers were found not guilty.

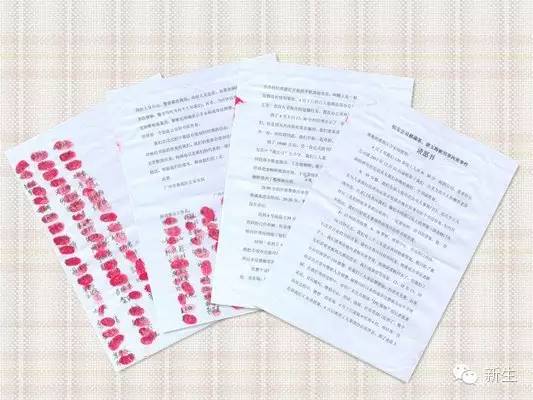

On June 2015, the relocation of a Shenzhen Artigas Clothing & Leatherware factory sparked a strike involving hundreds of workers. The management attempted to buy off a female worker named Wu Weihua by offering her 150,000 RMB, and then fired her when she refused. More than 10 workers were taken away on the first day of the strike, including Wu Weihua. On the same night, they were all released except Wu. According to the police, she was ‘seized by the factory’ (是工厂抓的), meaning that the management told the police to detain Wu in particular. She was given the criminal charge of ‘obstructing public administration’ (妨碍公务). One month after the strike, the police detained five more workers. This time it was the police who ‘bargained’ (讲价) with them, claiming that if they ended the strike and accepted 500-1,000 RMB per person as compensation, then the detained workers would be released. Reluctantly, the workers agreed. The five detained workers walked free, but Wu remained on trial.

As the economic situation deteriorates, capital is relocating to places with cheaper labour in order to intensify exploitation. In this context, workers’ struggles will inevitably become more intense, and their repression more severe. This trend can be seen in the increasing treatment of striking workers as criminals, and the de facto treatment of strike actions as a crime.

Facing such repression, workers have no choice but to unite. We must protect our brothers and sisters! We need to remember that the rights we enjoy today are the results of struggles by workers unprotected by laws. The use of the law to suppress workers is never hard to understand, because the people who devise laws never include any workers!

Chuang editorial notes:

- On the 2010 strike wave, see “Workers’ autonomy: strikes in China” by Mouvement Communiste and Kolektivně proti kapitálu.

- See “Free the Women’s Day Five! Statements from Chinese workers & students,” “Gender War & Social Stability in Xi’s China: Interview with a Friend of the Women’s Day Five,” and “How “feminism” became a household word this Spring Festival.”

- At least one ongoing case, where workers are on trial for criminal charges, has been omitted from this piece at the author’s discretion.

- According to Chinese law, an ordinary ‘administrative detention’ (行政拘留) may last only up to 15 days. Part of the ‘criminalization of labor actions’ is the switch from administrative to ‘criminal detention’ (刑事拘留), which requires a criminal charge and may last up to 37 days, often followed by criminal proceedings and further detention or imprisonment. These security guards thus expected no more than 15 days of administrative detention.

Greek translation here: http://prolenet.gr/2016/03/02/k%CE%AF%CE%BD%CE%B1-h-%CF%80%CE%BF%CE%B9%CE%BD%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%BF%CF%80%CE%BF%CE%B9%CE%AE%CF%83%CE%B7-%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD-%CE%B1%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%B3%CE%B9%CF%8E%CE%BD-%CE%B1%CF%80%CF%8C-%CF%84/